As history chronicles the decade-long shit storm of the Mad King’s reign, this past week stands out as beyond important, beyond life changing. By comparison, January 6 was a Girl Scout meeting.

This week we all got a pop quiz on Wall Street, the bond market, trading deficits, the strength of the U.S. dollar. Then, he threw in a little international studies, the Chinese Communist Party, the EU and points in between, including tariffs on penguins.

“This sucks” doesn’t quite get at what’s happened and what’s likely still coming down the Trump Train track. U.S. economic policy is tied to his Art of The Deal, a book published in 1987 just as plant closings and foreign imports were picking up steam. It’s questionable on so many levels, not the least of which are his four bankruptcies. That’s an EPIC FAIL! Why should this maliciously stupid person be anywhere near the markets? Scott Bessent, please hide the Sharpie.

Yet, the turmoil of the tariff poison pill dilutes the credibility of a critical MAGA goal. In America’s heartland many communities remain devastated by globalism 50 years after we first heard the word. These places have been through many presidents, many economic policies, multiple generations of local, state and national leaders, and countless technological and societal breakthroughs. No matter. In 2025, life in these towns has gone from hopeful to impoverished to death spiral. It’s not quite captured in the bureaucrat-speak “onshoring our manufacturing.”

One is my hometown, McKeesport, Pennsylvania. I’m going to share with you what happened there and why. As the negligent narcissist drives the world off a cliff, McKeesport needs our attention with REAL leadership and policies. Further, bringing these towns back is absolutely achievable from the richest and most powerful nation on earth. The story comes from work on a book my co-author Gary Antonella and I hope to publish sooner, not later. Because later, there may be nothing left. Note, it’s a long read.

A Librarian Has A Story To Tell

Jo Ellen Kenney is ready to share her memories of a difficult time. She has relevant opinions. Talking with a reporter she met just moments before is her way to be heard. In the old days, she would have spoken to the McKeesport Daily News, the town’s heartbeat of a newspaper that folded in 2015 after 131 years.

We sat at a table in the Children’s Room in what once was her domain, the Carnegie Library of McKeesport. Jo Ellen is still every bit the Rust Belt warrior she’s been since the mills went down in the 1980’s. Social worker and advocate wasn’t her job or training, weren’t tasks she sought out. Still, she’s done plenty of both, because she cares deeply about the future of McKeesport. Let’s say she has opinions.

Now retired, Kenney was director at one of the original Carnegie libraries for nearly 25 years. McKeesport’s opened in 1902. She worked there most of her adult life. Her days were filled with story time, kids researching book reports, wrangling volunteers, and pitching city council for grants. It all changed in the late 1980’s as McKeesport was pushed through a portal of 20th century globalism into a doom loop of poverty, blight, and terribly ineffective governance. In the 21st century she believes strongly the story needs to be heard.

“One day, I had a dad show up at story time with their child. That was unheard of. I never saw a dad before. But, the Mom went out and got a job at McDonald’s while the Dad was waiting for an (unemployment benefits) extension of three weeks, of 13 more weeks, of 10 weeks. That’s how they were living. Then, the Dads started coming to story time.”

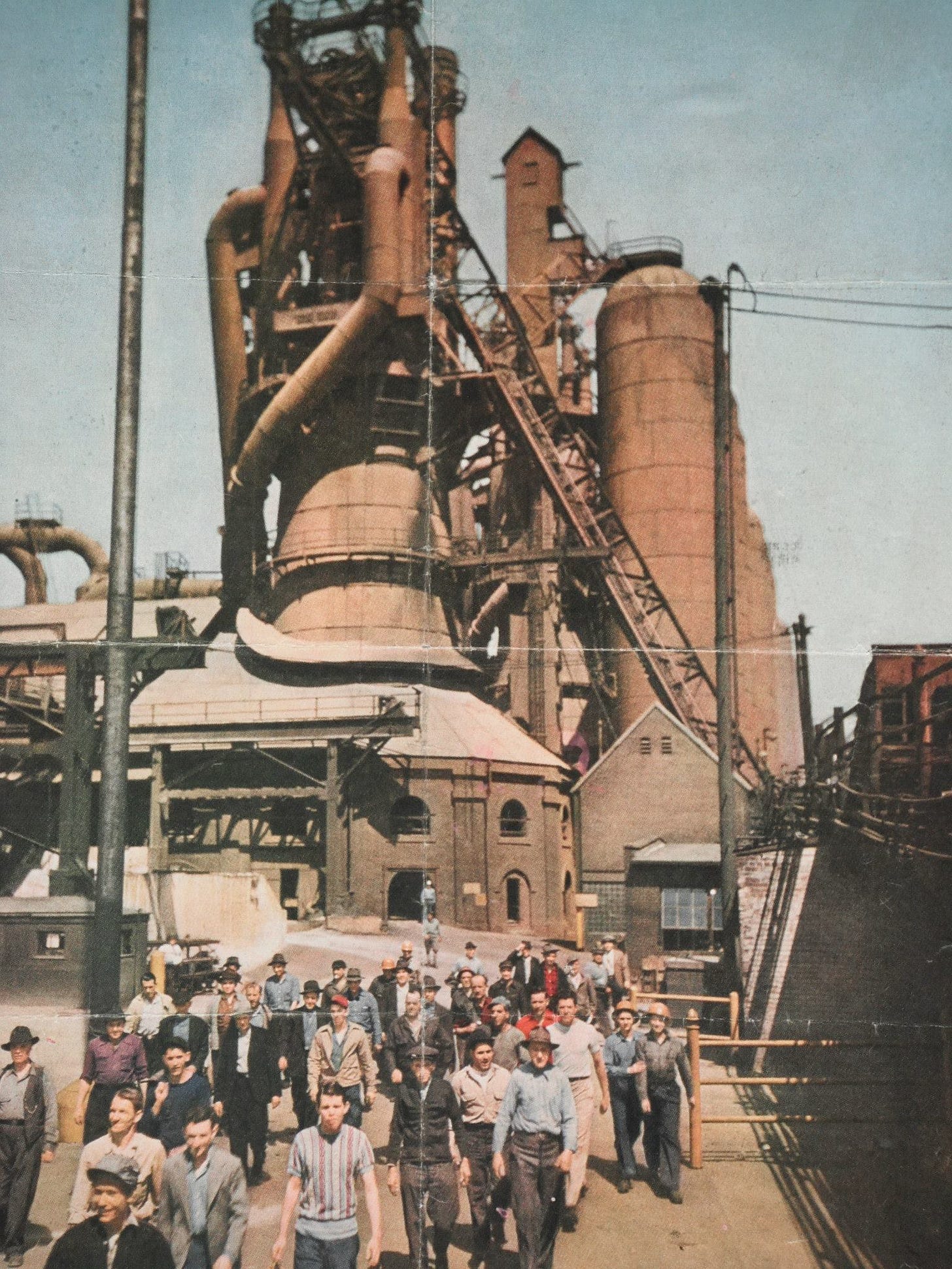

It was the late 1980’s. Just a few years earlier, McKeesport Dads had no time for taking kids to the library. “Day turn,” “3 to 11,” “night turn,” “long turn” – local slang for eight hour shifts, the long turn being 24 hours – kept them busy at one of the massive United States Steel (USS) mills lining the Monongahela River, by barge or rail just 10 miles from Pittsburgh, the “Steel City” itself. Combined, the mills were a giant integrated production line turning out steel and specialty metals, building a prosperous post-war America.

“Coke” manufactured at Clairton Works’ batteries – coke being a super fuel derived from coal not a soft drink – fired the blast furnaces at McKeesport’s National Tube, the world’s largest pipe manufacturer. Clairton coke fired the Bessemer process for specialty steels at Duquesne Works, and Braddock’s iconic Edgar Thompson Works known as “ET.” ET was Andrew Carnegie’s first mill, built in 1875 and named for the owner of the Pennsylvania Railroad, whom he hoped to impress. At West Mifflin’s Irvin Works, steel plates and rolls were shaped for autos then sent across the river to GM’s Fisher Body plant. At the historic Homestead Works, where seven striking workers and three of management’s Pinkerton Detectives died in an 1892 riot, ET’s steel is formed for rail cars and skyscraper frames.

USS was the big dog here but not the only player. Smaller plants were shoehorned along the flats of both the Youghiogheny and Monongahela Rivers, which met at McKeesport – Firth Stirling, Fort Pitt Foundry, USS Christy Park Works, and Kelsey Hayes in McKeesport; Mesta Machine in Homestead; Hays Army Ammunition Plant in Pittsburgh. Ruling the foothills east of Pittsburgh and into the Turtle Creek Valley were the imposing Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, the Westinghouse Machine Company, and Westinghouse Air Brake.

Dads and their families lived large, the benefit of dream labor contracts paying in 2025 dollars 85,000 to 110,000 a year. Thanks to the United Steelworkers Union (USW) the largess, included “the 13 weeks,” awarded every five years. It was a summer off at full pay. Dads spent the hot days at their cool second homes, “cabins” in Pennsylvania’s Laurel Highlands or at a favorite retreat in Deep Creek, (the locals say “crick”) Maryland. Their absence allowed USS to keep labor piece while re-tooling its operations without lay-offs.

In short, a mill job felt immortal, work so good, it made for difficult choices. Here’s legendary McKeesport labor writer John Hoerr from his comprehensive tale of the death of American steel - And, The Wolf Finally Came:

“For young men in the mill towns of those days, there was a very tangible sense of having to make an implicit bargain with life from the outset. There were two choices. If you took a job in the mill, you could stay in McKeesport among family and friends, earn decent pay, and gain sort of a lifetime security (except for layoffs and strikes) in an industry that would last forever. You traded advancement for security and expected life to stick to its bargain. …In a sense, everybody growing up in America must decide whether to stay or move on. In the Mon Valley, however, the very presence of the mill on the riverbank, its gates flung open to young men (not women and not Blacks in the better jobs), forced you to make this choice.

Many chose to stay home. At the peak during and just after World War II, nearly 350,000 toiled in the “Steel Valley” and “Electric Valley.”

An Early Warning

The Pittsburgh region, including McKeesport and the Mon Valley had been warned. Change was coming and not the good kind. Dr. Edgar M. Hoover, Professor of Economics at the University of Pittsburgh and a staff member on the Council of Economic Advisers in Washington, D.C., authored a 1963 report entitled A Region In Transition. It analyzed demand for steel products against the number of workers needed to meet it. Hoover’s figures: post-war steel jobs peaked at 110,000 in 1960 and were projected to fall to 63,000 by 1985, a drop of 57%. American steel markets were contracting.

The Cassandra call came as the region was still in its post-WWII zenith. A doomsday prediction proved difficult for local leadership to embrace. It was largely ignored. Looking back at that time, even from the viewpoint of my eight-year-old self, it wasn’t hard to see why.

Simply, McKeesport in the 1960’s and 70’s was the kind of dynamic community urban planners still try to duplicate all over the world. The largest city next to Pittsburgh, its walkable, thriving downtown would be the equivalent of a high-end shopping mall today. From fine dining, to specialty shops, to department stores, to five and dimes, to grocers, to movie theaters, to greasy spoons, banks, and bars, and pool halls – downtown McKeesport catered to the wealthy and the middle class as a leading edge commerce center. Its extensive Christmas, Veteran’s Day, and Memorial Day parades packed the sidewalks with shoppers who watched fashion shows on the Cox’s Department Store balcony, filled the bars and restaurants, and caught a movie at the Memorial Theater. And in all the fun, if anyone got sick or hurt , the very modern McKeesport Hospital was close by.

McKeesport’s political and merchant class was educated, energetic, focused and playing for keeps. Their newspaper The Daily News, drove home Establishment expectations for governing, business and behavior. Leadership wasn’t shy about flexing its muscle to keep the rabble in line, deploying an aggressive police force with a law and order reputation. The head-busting cops would become a flashpoint in the 60’s and 70’s in a couple of neighborhoods, notably “the projects” in Crawford and Harrison Villages, Lower 10th Ward, and the Black neighborhoods centered along Walnut and Market Streets.

McKeesport was also leading edge in education, an enormous urban district with pipelines to area universities and business schools. The local schools, especially their vocational training, fed job-ready workers to the mills and retail sector. Its prominence enticed an Allegheny County Community College and a Penn State branch campus to open in the 1960’s when the push for getting a college education was gaining momentum.

But, the mills ruled. At shift change, the “mill hunks” (local slang for a steelworker) went home to tidy middle class houses on the hills above their workplace falling asleep to the clanging of rail cars while blast furnaces painted the sky orange.

McKeesport’s neighborhoods were both ethnic enclaves and religious centers. You could identify the European roots by the parish. St. Perpetua for the Christy Park Italians. St. Peter’s for German immigrants along the Youghiogheny River. St. Mary’s Polish. St. Mary’s German. St. Mary’s Romanian Byzantine Catholic Church. Sacred Heart Croatian Catholic Church. Holy Trinity. And on and on. Some had elementary schools. All had summer fairs with gambling and beer. In August, the churches came together to show off their culinary traditions at the annual “International Village” staged in spacious Renzie Park. Rivalries aside, all agreed McKeesport was a proud, happening place to live and work.

Then Came Globalism

The hills forming the Monongahela River Valley with its mighty steel mills and powerful downtown McKeesport retail, also fostered isolation, a mindset of everything-I-need-and-need-to-know-is-right-here. It kept the world out, including news that steelworkers with bullet proof contracts and giant steelmakers with huge domestic market share were under threat.

The world of the 60’s and 70’s was rapidly changing. In the years following World War II, the Marshall Plan rebuilt Europe, and Douglas MacArthur reformed Japan. Both had strong, productive industries and workforces searching for markets. Enter, the U.S.

In modern plants, some with robots, all with collaborative management-labor relations, Japan and Germany produced high quality steel at lower cost than American companies. Korea and Brazil weren’t far behind.

The Mon Valley was shocked when construction of the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline in the 1960’s relied not on McKeesport National Tube, the world’s largest pipe manufacturer, but Japan. Not only was our once mortal enemy physically closer to the oil fields than McKeesport, cutting shipping costs, its pipe was better. Notably, United States Steel did get a contract for a 2,000-mile natural gas pipeline from Alaska through Canada to the States. But it remains uncompleted, caught up in the grind of environmental and economic disputes.

In the auto industry, imports were grabbing American market share with affordable and reliable compact vehicles. “Datsun,” the forerunner to Nissan, introduced Californians to a cheap, reliable “little red pickup,” its simple design perfect for everyday needs. Germany’s Volkswagen offered a high MPG “Golf” and later a “Rabbit” hatchback to go with its iconic VW Beetle and Bus, attractive cars as pump prices spiked. Honda debuted its own “N600” hatchback to join its many motorcycles on U.S. roads.

In the meantime, America’s auto and steel industry wrestled with a quadruple threat.

Its labor was too costly.

Its products were low quality. The steel easily rusted. Big, inefficient engines guzzled gas in cars with low reliability.

Its plants, some approaching 100 years old, faced obsolescence unless they were rebuilt and retooled.

U.S. trade policy wasn’t tough or consistent on penalizing the “dumping” of low-cost foreign steel in American markets. The concept of world markets and interconnected supply chains was beginning to take hold. The U.S. wanted overseas partners, not adversaries.

Steel and auto management brought their case for relief to the United Steel Workers and the United Auto Workers. They needed better contracts, so they could invest in new, modern plants. Without a change lay-offs and plant closures were coming.

The response was cold and direct. First, we don’t believe you. Second, we don’t trust you. Third - this coming from workers who fought wars in Germany, Japan, and Korea - we know we’re better than those guys. No, we’re not giving up 13 weeks. We’re not taking pay cuts or buyouts or conceding minimum staffing requirements. There will be no robots in these mills.

You know what happened next. As the plants closed, Dads found their way to story time at McKeesport’s Carnegie Library.

“There were young families that had houses and boats and trucks and cars. Living high, and all of a sudden there was nothing. They then proceeded to lose all their luxuries in life,” Kenny remembers the crash 40 years later as if it was just last week. There was desperation and denial.

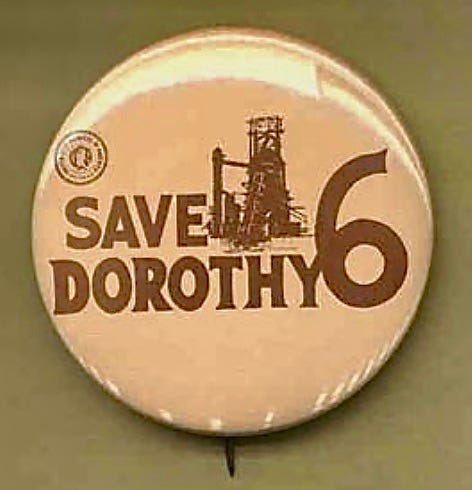

“Every neighborhood had dads who were ‘mill hunks’ They just denied the whole situation. They were taking their kids over to Dorothy to protest, and I’m thinking, wow. They were taking their kids with them. It seemed to me somebody ought to be studying this denial. Who was going to burst their bubble and tell them the truth and they believe it?”

The denial played out on the evening news, in the papers, on radio with stories of steelworker protests. “Over to Dorothy” referred to the demonstrations at Duquesne Works’ “Dorothy 6” furnaces – named for Dorothy Helen Rice Worthington, the wife of Leslie Worthington, once the president of U.S. Steel.

“The mills will come back” was a deep belief of thousands of unemployed steelworkers, convinced the decisions to close would be reversed. Otherwise, if there was a war, who would make the steel for tanks, ships, and planes? The situation became irreparable as 22,000 USS workers went on strike in August of 1986, remaining on the picket lines for 187 days.

“I heard them, ‘if only we get three more weeks. If only we get 10 more weeks of unemployment, then we’ll be going back,’” Kenney recalls conversations with Dads after story time. “It’s like, wow, I don’t know that you’re going back. I didn’t want to burst their bubble. It was just a denial that was across the board.”

In the face of this disbelief, Dorothy 6 was demolished in 1987, the same year USS closed National Tube. The mill first came to McKeesport in 1872. 22,000 worked there at its peak. 22 remained on the last day.

Collapse

National Tube never reopened, nor did Duquesne and Homestead Works. ET, Clairton Works, and Irvin Works are operational with just 3,000 people as the combined “Mon Valley Works.” United States Steel dropped “Steel” from its name in the mid 1980’s when it diversified into energy with the purchase of Marathon Oil. Today’s “USX” is for sale and ironically, the top suitors include Tokyo’s Nippon Steel and Ohio’s Cleveland Cliffs, which has major operations in Canada. USX favors Nippon, but the Trump administration said this week worries over national security make Cleveland Cliffs a better fit.

Without its steady and reliable customer base, and with the emergence of shopping malls, once-muscular and always arrogant downtown McKeesport atrophied as the 1980’s ended. The merchants tried to adapt, but retail was going global too. Too many uncontrollable forces simply overwhelmed them, including a massive fire destroying multiple blocks in 1976.

Stores closed. Office buildings emptied. The G.C. Murphy Company, which launched five and dime stores in the early 1900’s and grew to over 500 stores nationwide, was sold to the Ames Department Store chain in 1985. Over the next decade, its corporate headquarters downtown was shuttered, as was its warehouse and distribution facility near the Youghiogheny River.

People who had known nothing but the Monongahela Valley left forever, looking for work in non-union auto plants in the South, an air bag factory in Arizona, in oil and chemicals in Houston.

“Some of them, I guess, those were the smart ones, just walked away and went south,” Jo Ellen recalls getting news of departures the old fashioned way, at the library’s checkout desk. “All of a sudden, no one lives in this house anymore. They would pack up and move south to find work.”

At City Hall, the mayor and council desperately tried to save McKeesport. Retraining programs came together while leaders worked to find tenants for a massive industrial park on the riverfront. Among the near successes over the years were another pipe manufacturer; an Echo Star call center; and most recently a medical marijuana growing operation.

And there were big ideas too. Richard Mellon Scaife, the right wing publisher of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review envisioned a state of the art printing plant to grow his media empire. He died before it could be built and his family scuttled the idea in a battle over his estate. The Rooney family, owners of the Pittsburgh Steelers and major gambling and horse racing operations in Florida, considered turning the mill site into a horse and dog racing track. Allegedly, Rooney and then Governor Bob Casey Sr. (no relation) shot down the project in a moment of religious conscience.

“He said, you know, I'm a Catholic, and I don't think we should do this,” Dennis Pittman told me in 2023 over lunch at a diner outside McKeesport. Pittman was City Administrator in the early 2000’s, on the forefront of trying to bring the town back. I can hear the disbelief in his voice.

“You gotta be kidding me. I mean, met with him personally, met with his staff. And he nixed it because we needed his approval. I fantasize what that would have done for this city. It would have put a Hilton Hotel in here, or a Hilton Express or something, and all the other stuff that went with it. Because, we had the landmass to do it, and it would have worked the math.”

Pittman is an intelligent man, highly experienced, and committed to finding a way to bring jobs back. Now retired, he still tries to influence decision makers. He knows navigating the city’s Democratic machine politics, however, has many trap doors and trip wires. Dennis has gotten sideways a few times in an environment where McKeesport’s biggest barrier to success is clinging to the way things used to be done. The “we’re smarter than you” attitude alienated area foundations offering to help, further isolating the town. The lack of technical expertise amongst city staff is glaring, as the pols work the edges, blame the media, and generally play the victim. Vision is almost nonexistent.

Visit the city, and you’ll see Exhibit A of industrial decline. The visual hasn’t apparently reached McKeesport’s political leadership, now caught in a Trump-like game seeking domination their predecessors could legitimately conduct in the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s. Then, the combination of old school pols and paternal business barons threw their weight around unchallenged. In their eyes, Mighty McKeesport needs no partners, no allies, no strategic planning. They believe the “Tube City” is still the bully on the block and only they can save it. The result is the gutted downtown, a high rate of poverty, and hundreds of empty lots where homes full of steelworker families once lived.

The Future

The McKeesport diaspora is large and quite vocal on social media, wistfully celebrating the town as it was long ago. Their Facebook groups focus on a kind of “Lost McKeesport” still alive and well in gauzy memories, old photographs and videos. The youngest of this group are entering their 70’s. They are the last generation with any direct tie or lived memory of the glory days long past.

Overshadowing the nostalgia is a feeling of disbelief. They’re stunned by the transformation of once vibrant and safe neighborhoods into abandoned homes awaiting city-ordered demolition or random torching by an arsonist; the absence of foundational commercial and governmental institutions including a much-missed daily newspaper; personal safety threatened by gang-driven street crime; desperate fear the two remaining community institutions – the hospital and the school system – will dissolve under the pressure of declining population and infrastructure.

McKeesport’s rescuers must be tough because the bad news never seems to stop. In the past year, an effort took hold to build out commercial and housing near the city marina and the Great Allegheny Passage, a bike trail on the Youghiogheny. Project funding was a million dollar grant from the EPA’s climate justice program. There was hope. Then, there was the Mad King’s flex.

“The EPA terminated that grant a couple of weeks ago without notice based on one of the president’s executive orders,” one of the planners shared the devastating news this past week. I’m not using the source’s name because the info was offered as background without attribution. The disappointment was palatable. “That grant was acting as a springboard for many of the revitalization efforts we’ve been working on. The path forward is murky at best.”

But Jo Ellen Kenney hasn’t left town, isn’t giving up, and even though she’s retired, wants her Carnegie Library to transform into a resource center available to anyone who could benefit.

“People still read books. Children need books. This is a blessing,” she nods toward a young man using a PC, “and a curse. The children walk in the door, jump behind there, and there they go. And it’s like how far behind are we? I thought I was behind when I went to school. The children are not behind when it comes to technology.”

Jo Ellen wants more tech and staff for training, research, navigating services to help children and adults. She’ll deliver her vision to anyone who will listen, even if it means running an obstacle course to get to this interview.

Driving here meant maneuvering around a closed bridge over a busy thoroughfare shutdown due to erosion around its support pillars. Then, she detoured past a massive sink hole in a main street leading to the library. The cash-strapped city has announced no plans to repair either. Though it’s discouraging, Jo Ellen brightens recalling a better, simpler, livable McKeesport.

“What can I say about the 50’s. It was a giant neighborhood. Everybody knew everybody. A block down, we had a grocery store, a drug store, a fruit market, a cleaners, a fire station. We didn’t have to go anywhere.” Her memory is clear, the sensory of the time still strong. “Your mother, my mother would send me down to Franklin’s market and tell the butcher she needed a good soup bone. That’s what I’d do and he’d wrap up a bone and I’d take it home. Evidently, we were going to have soup for dinner!”

Jo Ellen is still willing to serve her city. She’s been on “many, many committees.” For now, she’s not waiting for Donald Trump to rebuild a steel mill.

Jo Ellen believes the comeback starts when America remembers McKeesport, Clairton, Homestead, Braddock, Duquesne, Lackawanna (NY), Youngstown (OH), Gary (IN) Akron (OH) and Dayton (OH).

Behind words like “Rust Belt” and “onshoring our manufacturing” are real people who are in a bad place.

People like all of us who deserve our attention and assistance.

Thank you for the article, Mark. My father retired as a police officer. My parents bought a bar. It had been a dream of my dad’s. It thrived for a couple years, then the Redevelopment came in and made them close down. The building was demolished. It broke his heart.

I tried mightily to get a teaching job in McKeesport but couldn’t even get an interview. I have lived in Central PA since the 1970’s and regularly visited family there for decades. I have family that stayed.

I taught in Steelton, PA, which reminded me of a mini McKeesport. It suffered the same fate with the steel mills.

I remain hopeful that someone will see the beauty in McKeesport and how valuable the land should be with close proximity to Pittsburgh.

We need people like you educating all of us.

Great article Mark, it brought back a lot of memories. I had neighbors who lost their mill jobs, one took his own life. It was tragic. At one point I was in-between computer jobs and found myself at the unemployment office in McKeesport. There along with many laid-off mill workers. The Governor put Re-training programs in place for computer jobs and we all had to take a test. I passed but they told me since I already had a degree in computer science that I could find a job on my own. Fair enough, and I did. But the mill guys were howling, they didn’t want computer training, they wanted they old jobs back. I thought to myself, how do I tell him “ his job is never coming back” ?

It’s sad and maddening what has happened to all these rust belt towns. Great article, I’m looking forward to your book, please keep me posted. Take care, Kathy